Working Mother explores the collision of identity, memory, gender roles, and labor — both paid and unpaid. Using vintage sewing patterns passed down from my mother and crayons borrowed from my son’s collection, I attempt to connect two generations: the one that raised me and the one I’m now raising. In doing so, I reflect on what it means to carry the title “working mother” — a title I proudly held until it was subtly, then explicitly, taken from me.

One week after informing my manager that I was pregnant with my second child, my job title changed. My team was reassigned. I was told the changes would help me “focus on what’s important,” but no one asked what was most important to me — or gave me a real choice. Six months after returning from maternity leave, I lost my job entirely (“Restructuring.”). Two months later, Roe v. Wade was overturned.

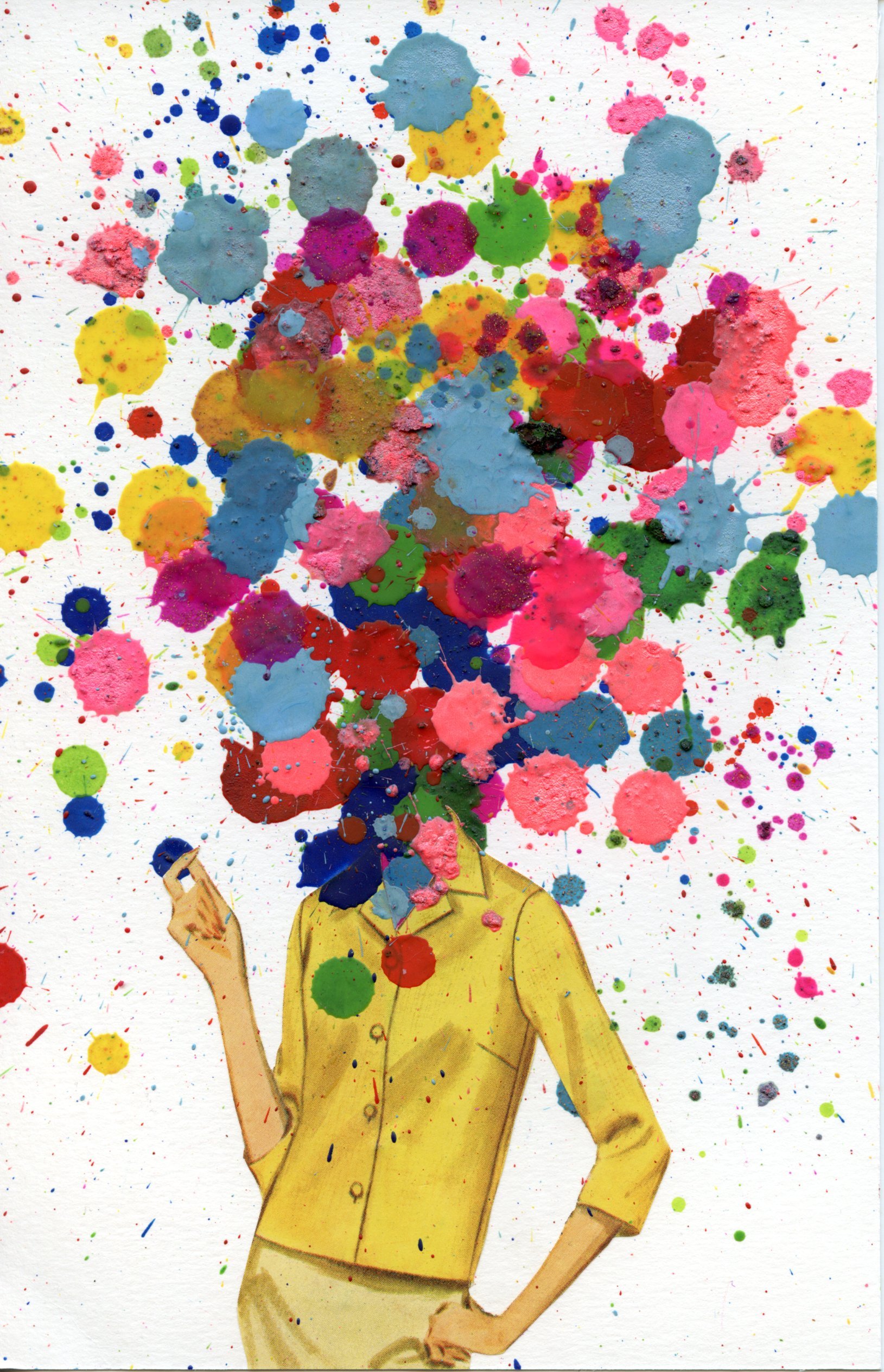

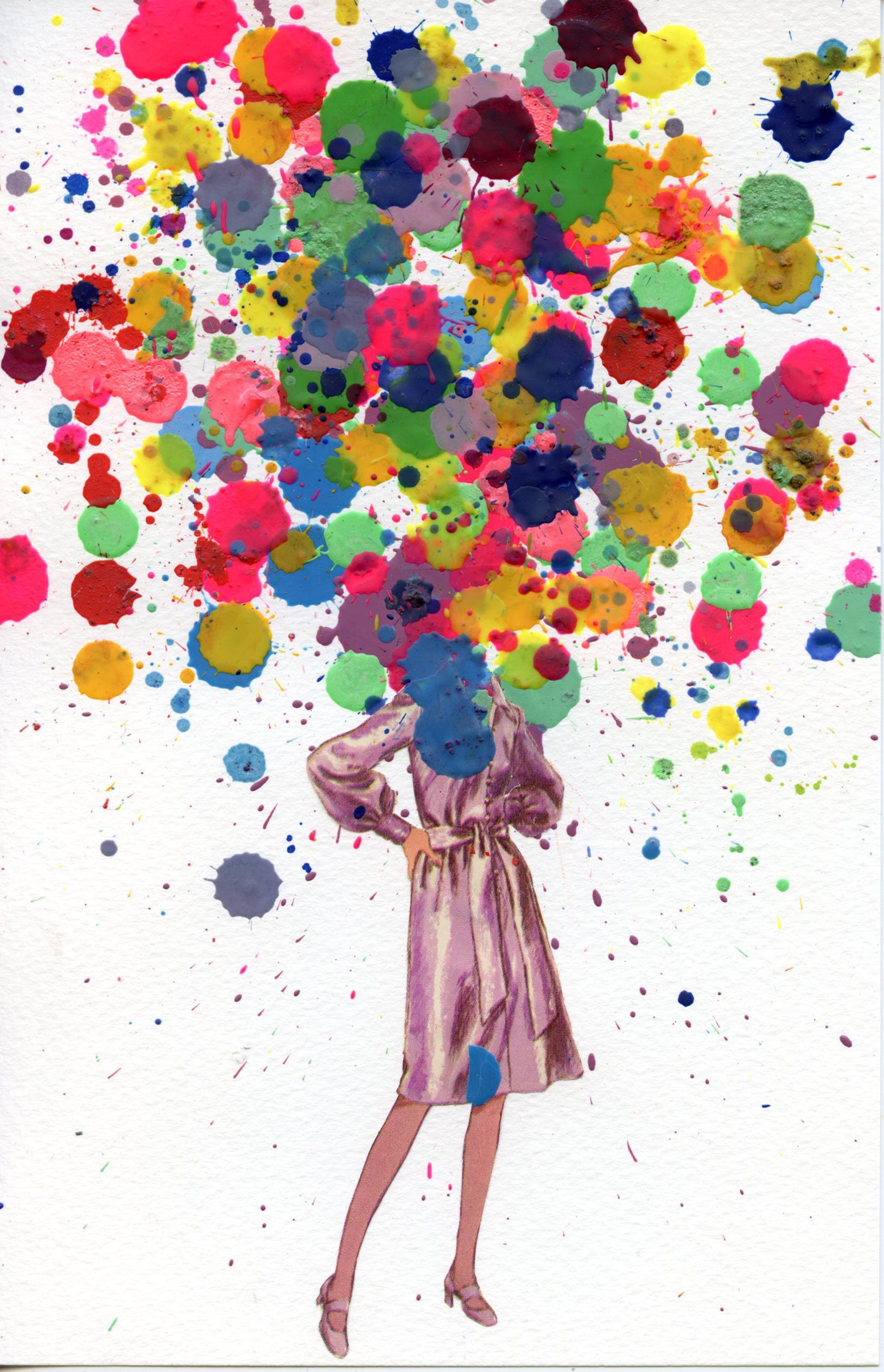

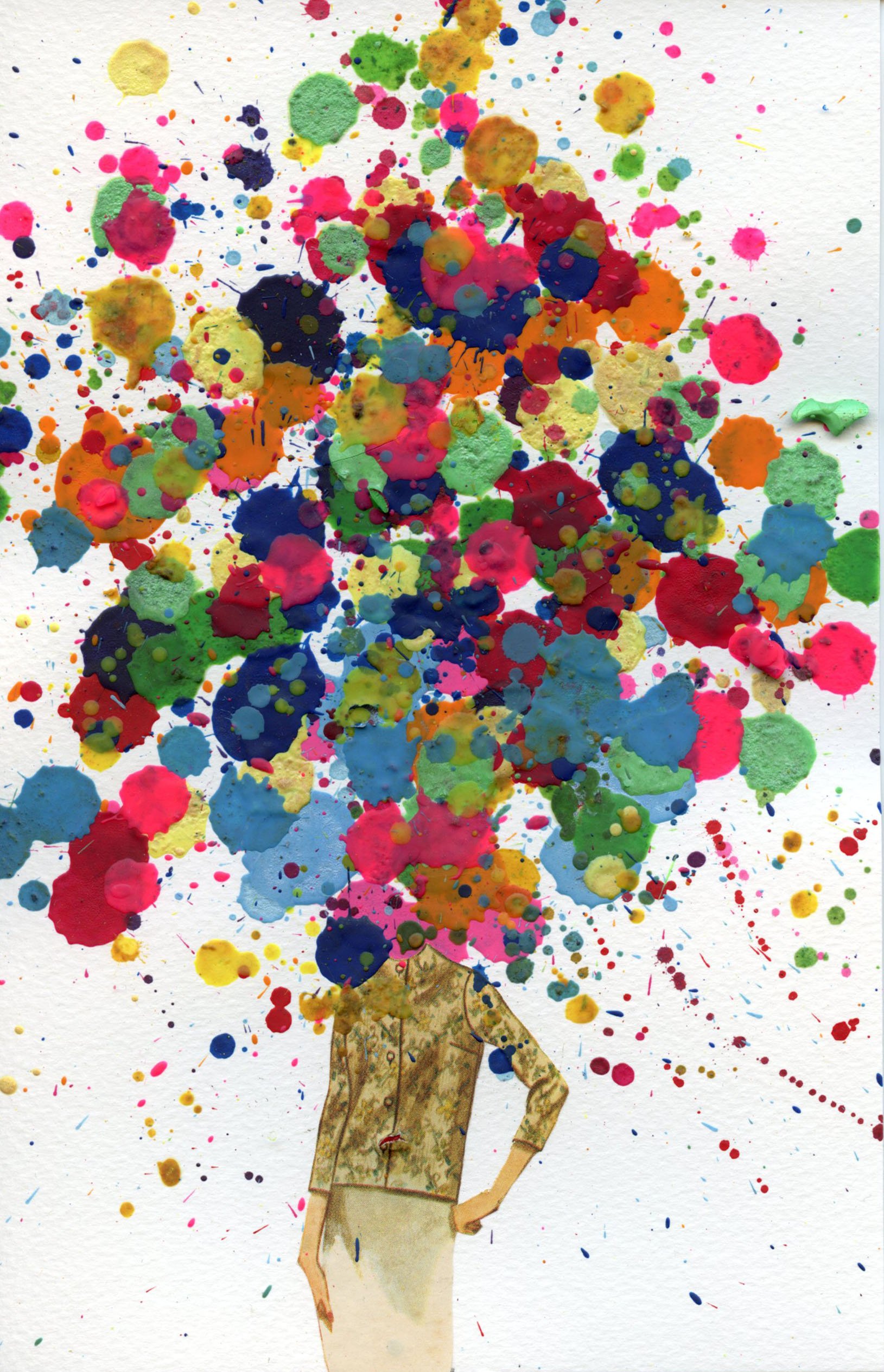

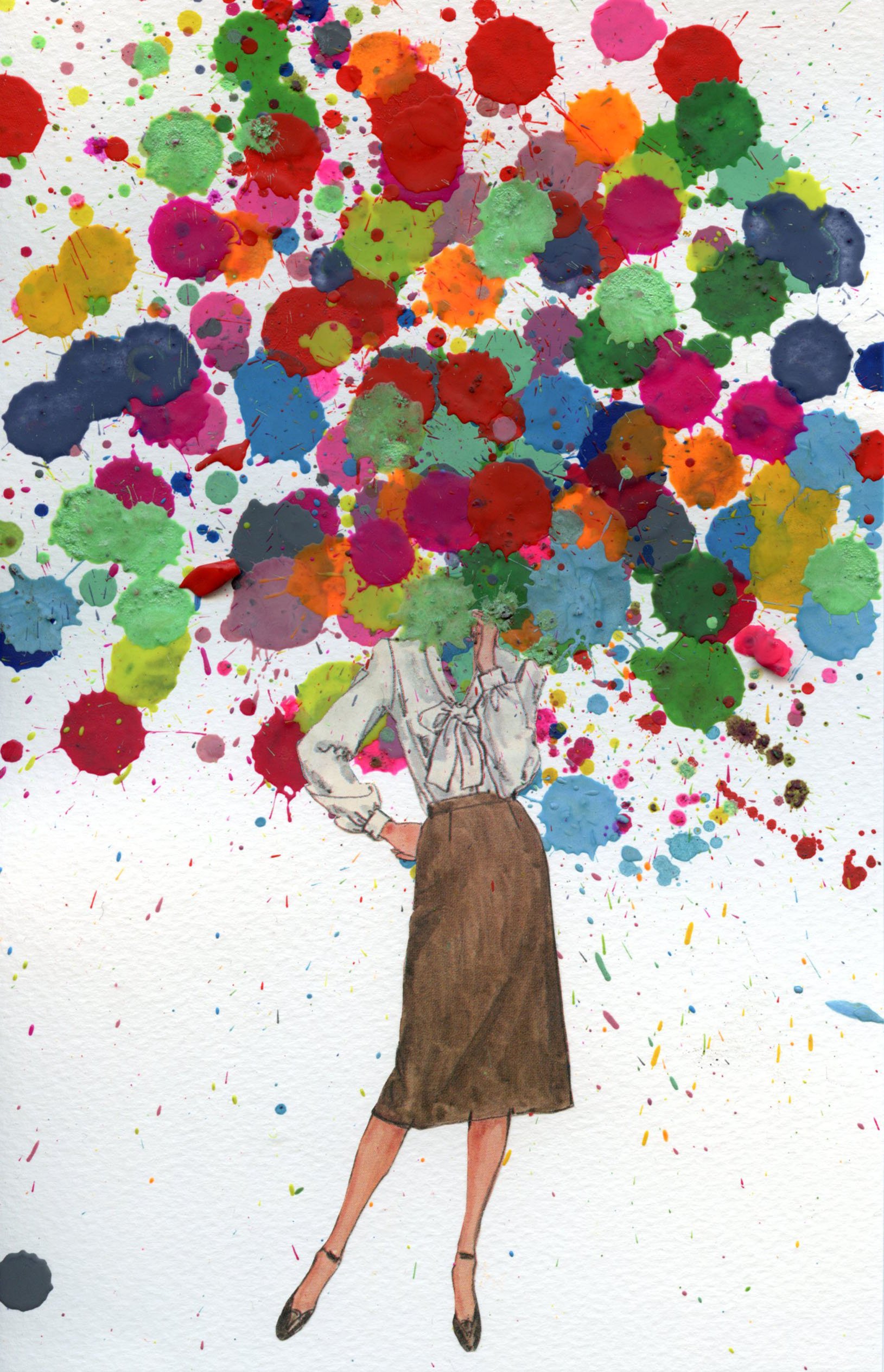

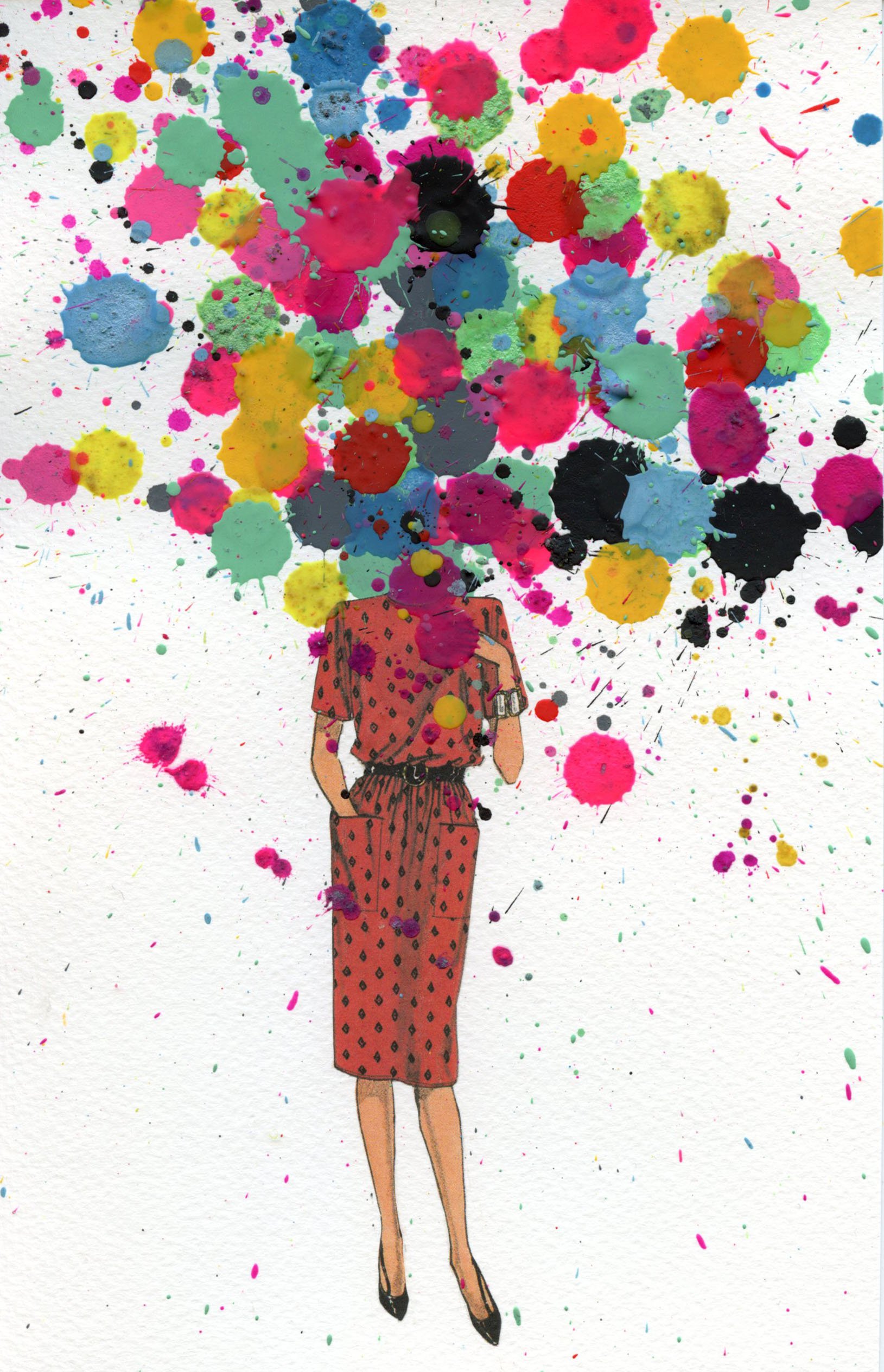

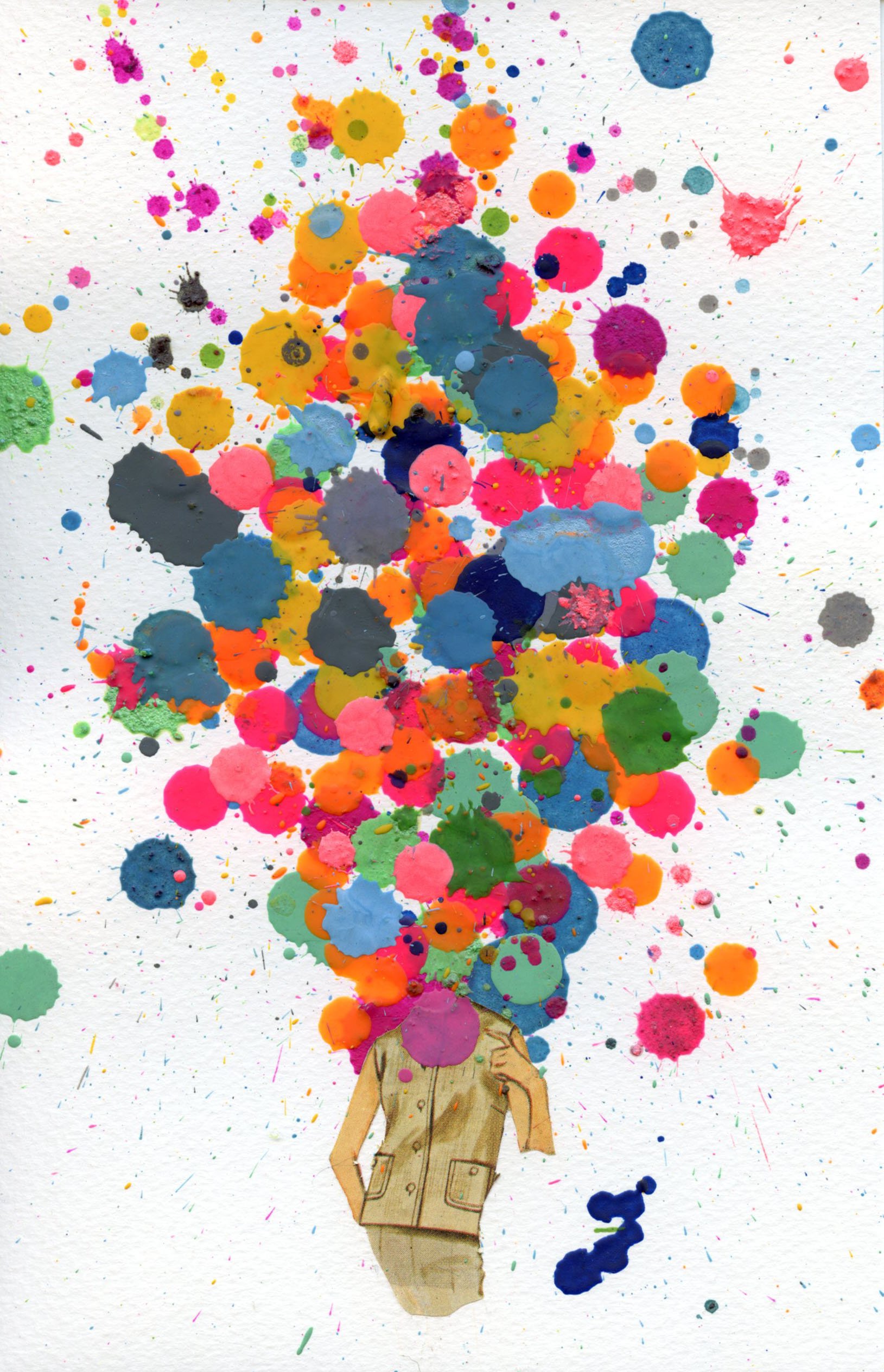

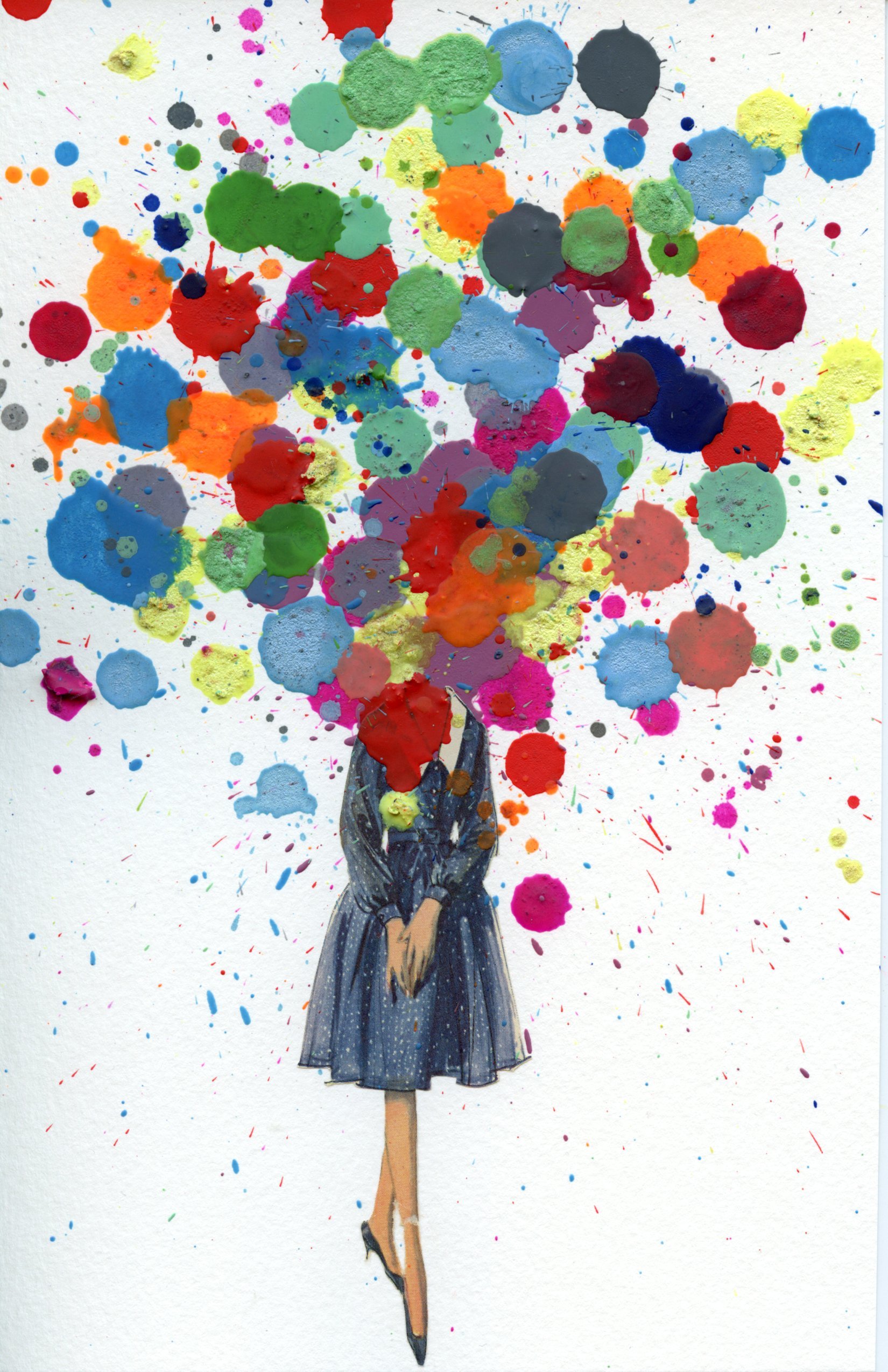

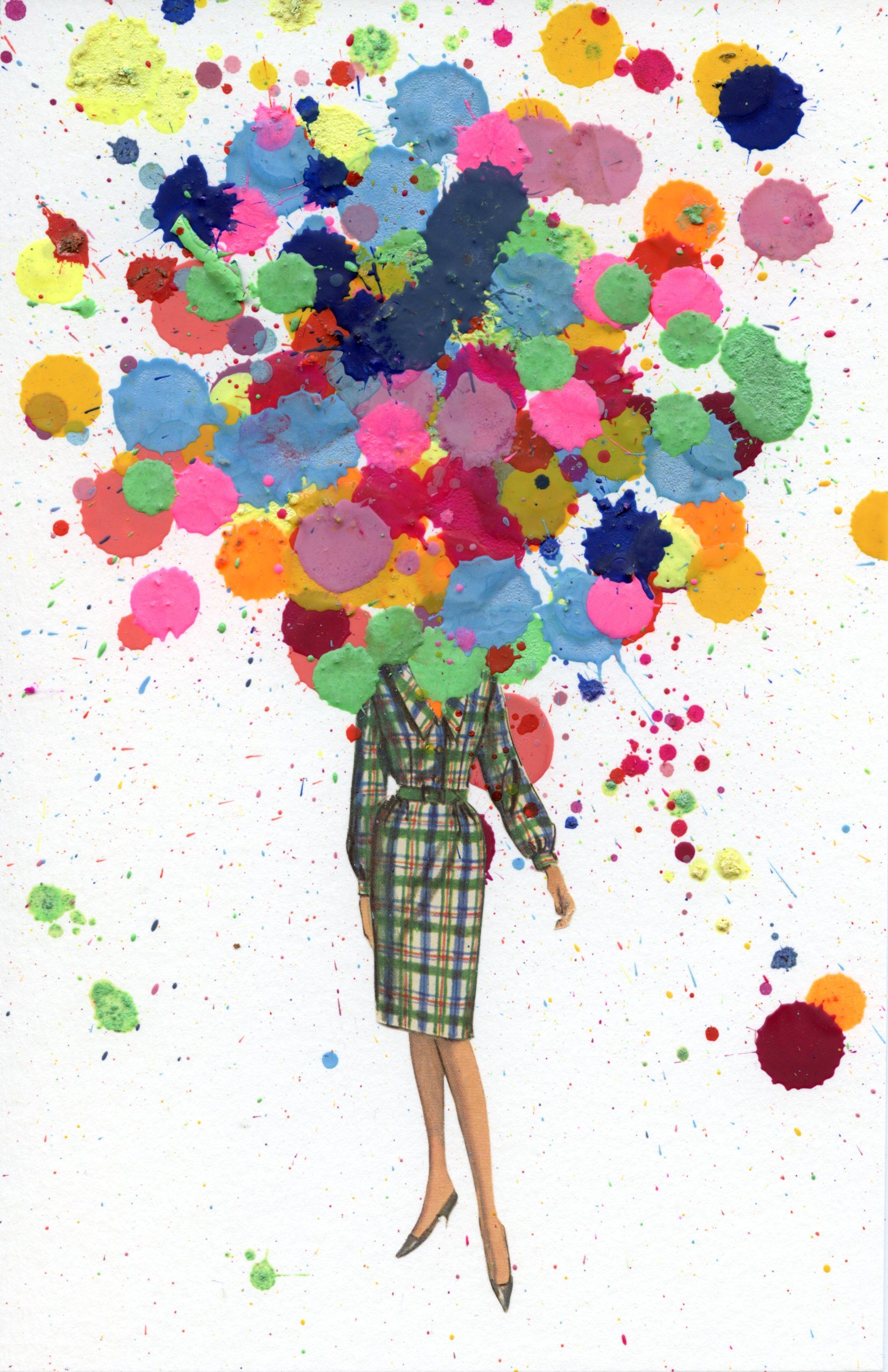

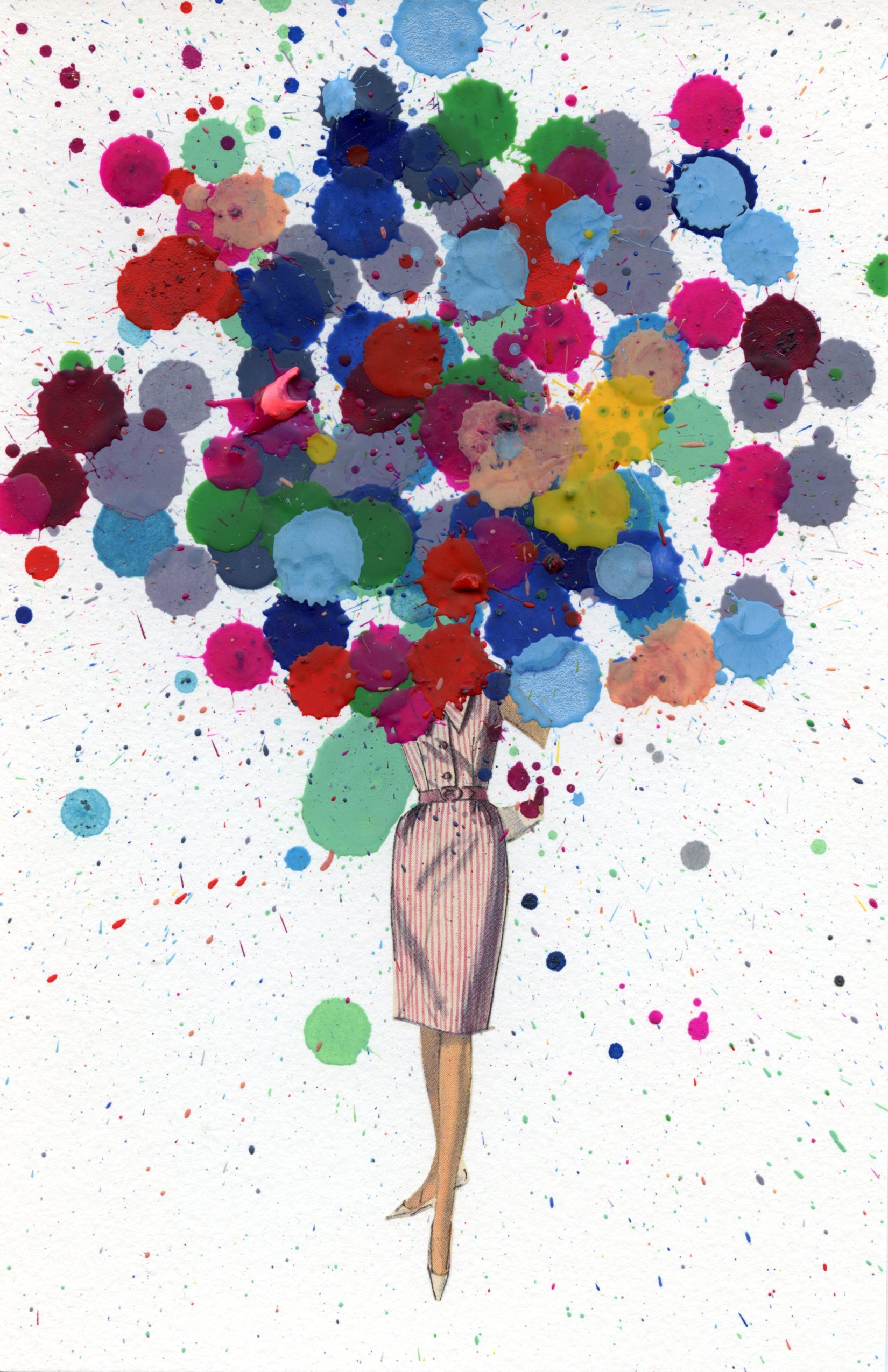

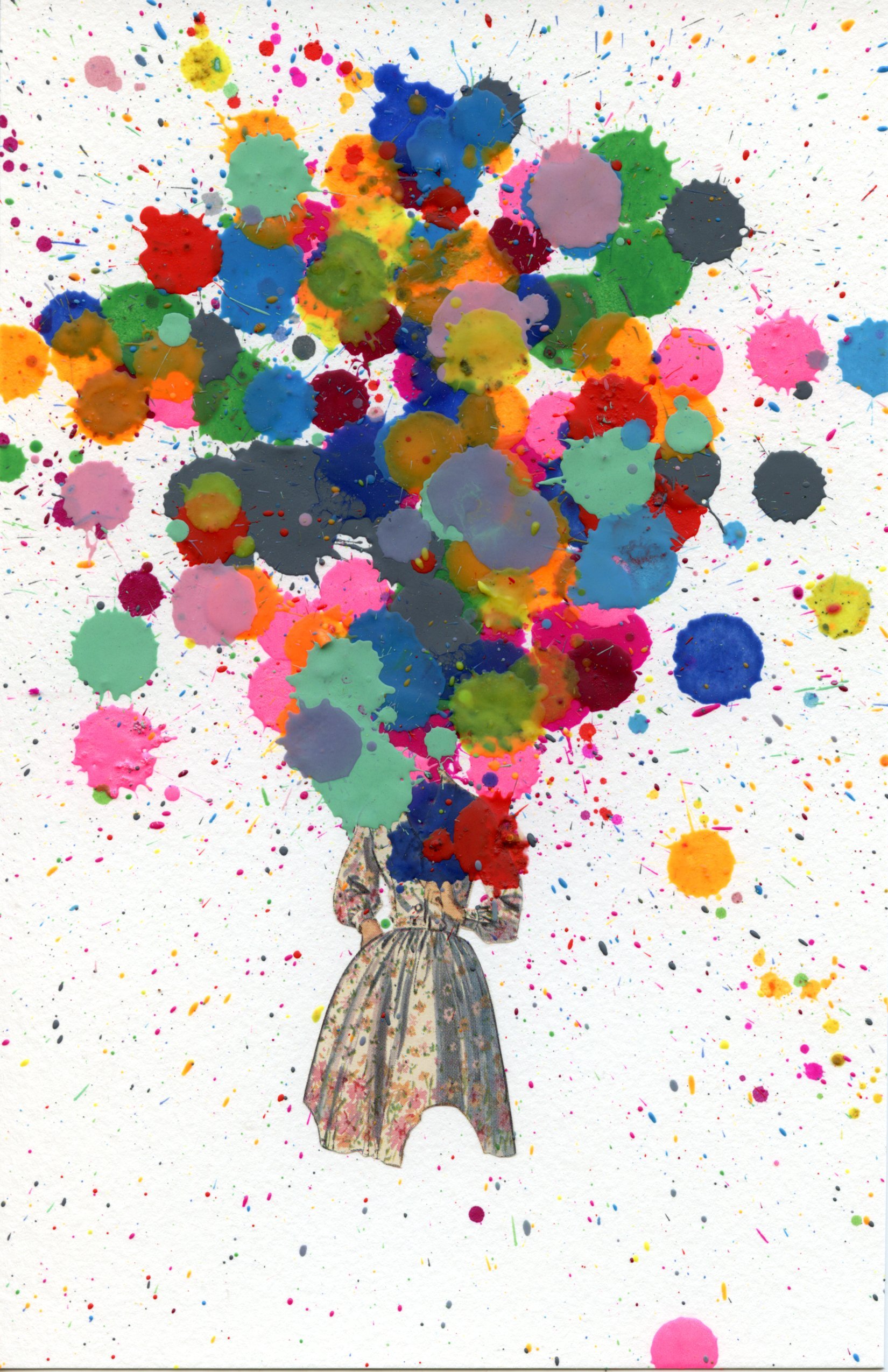

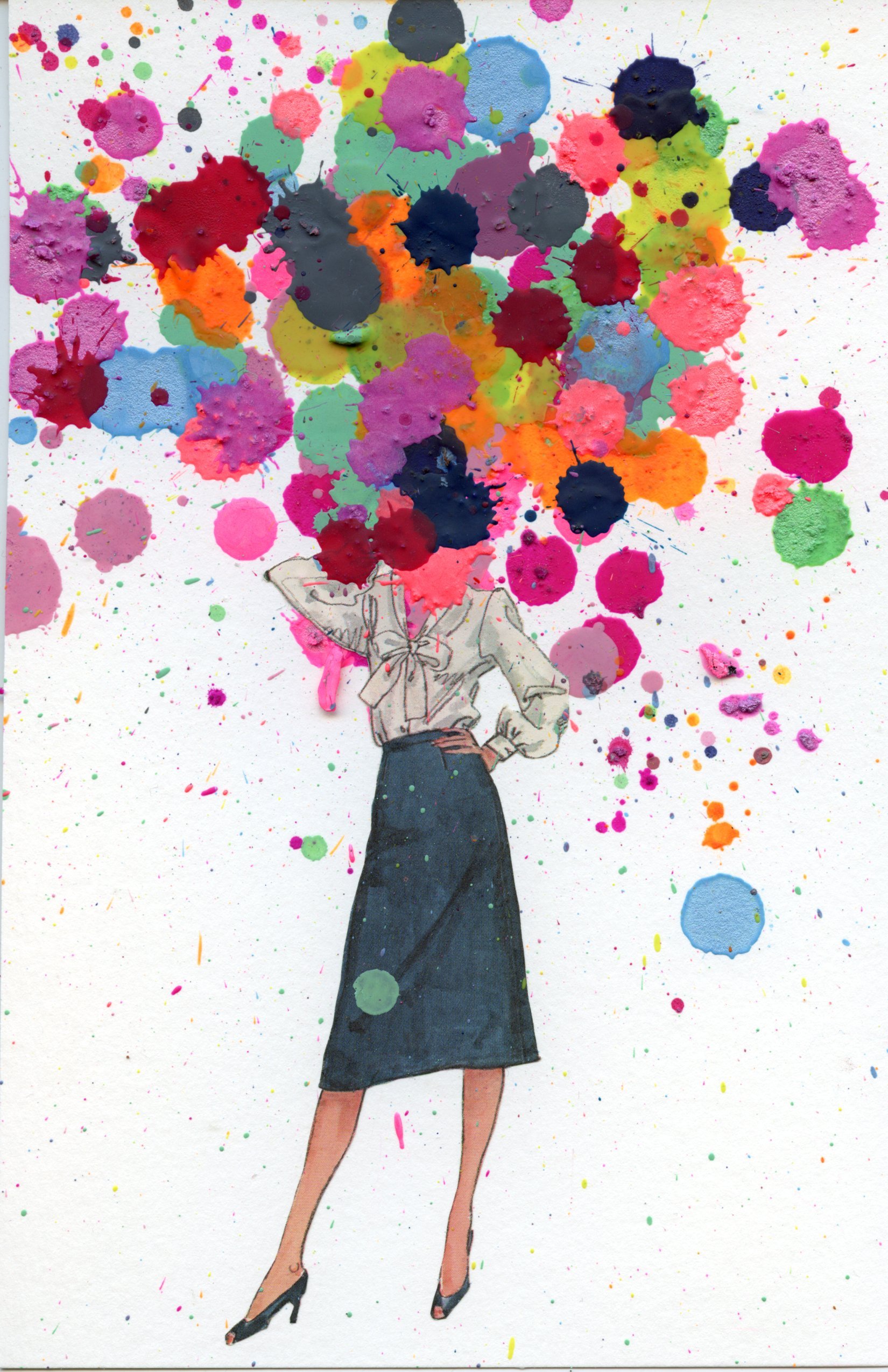

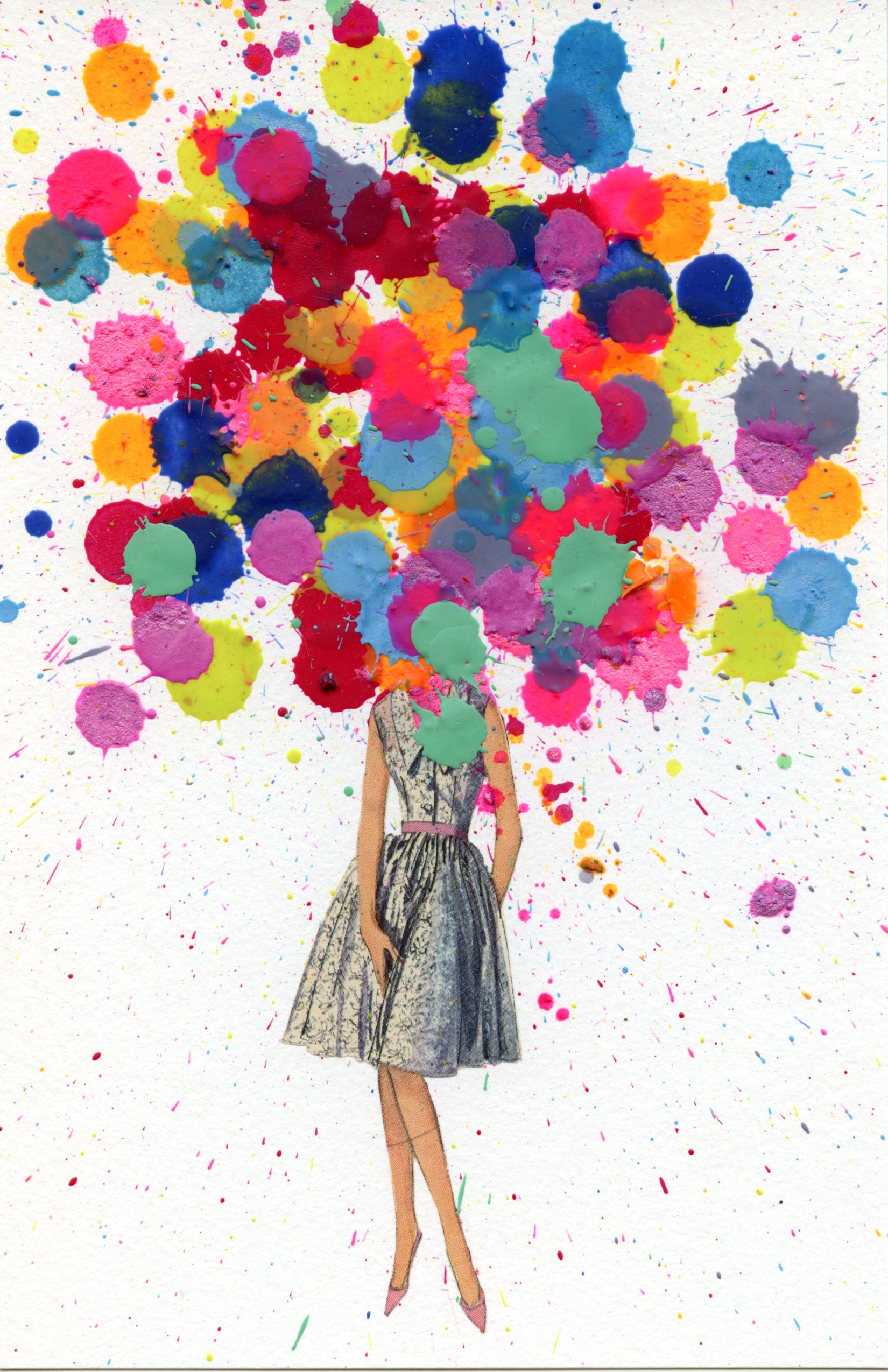

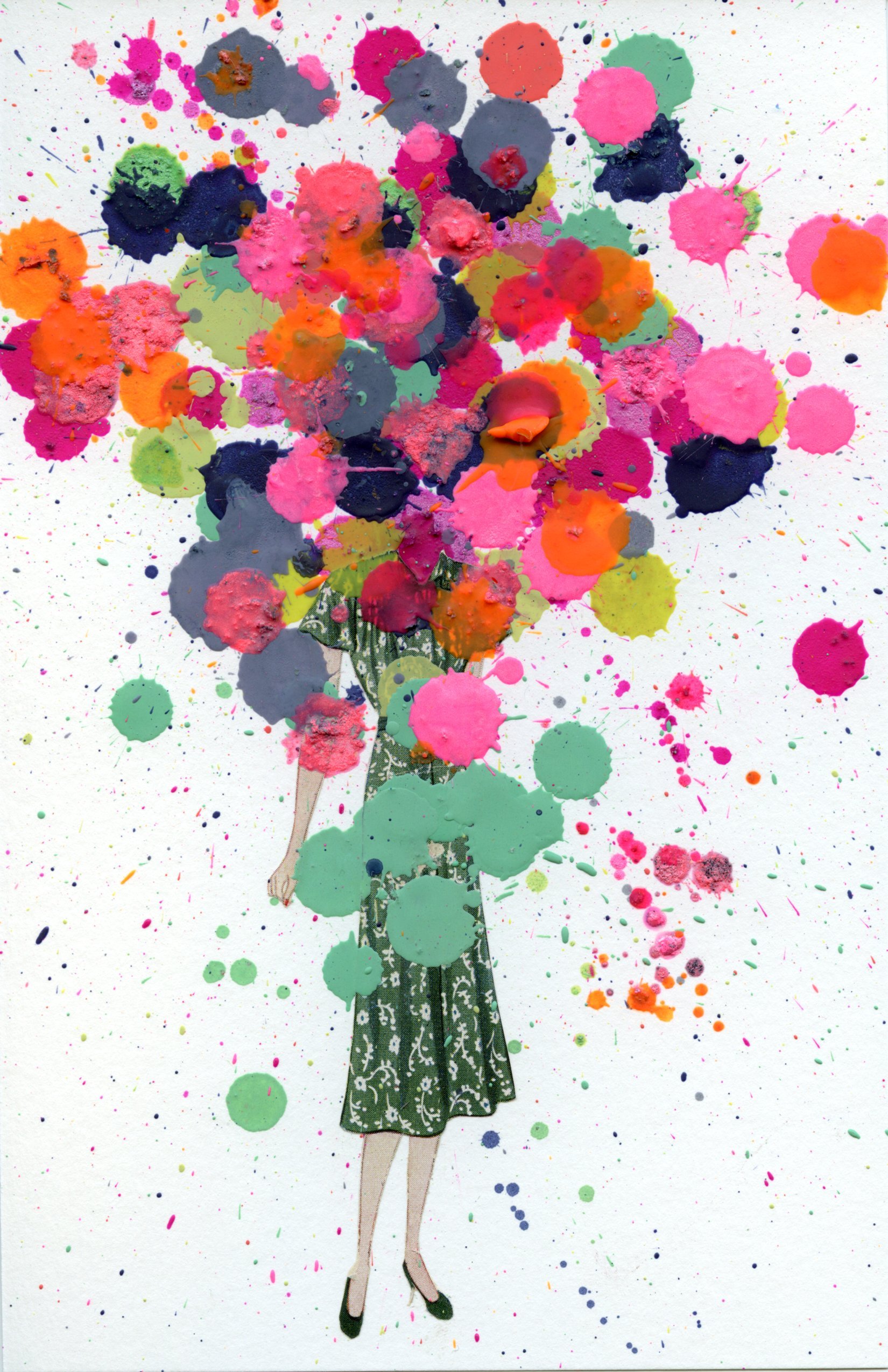

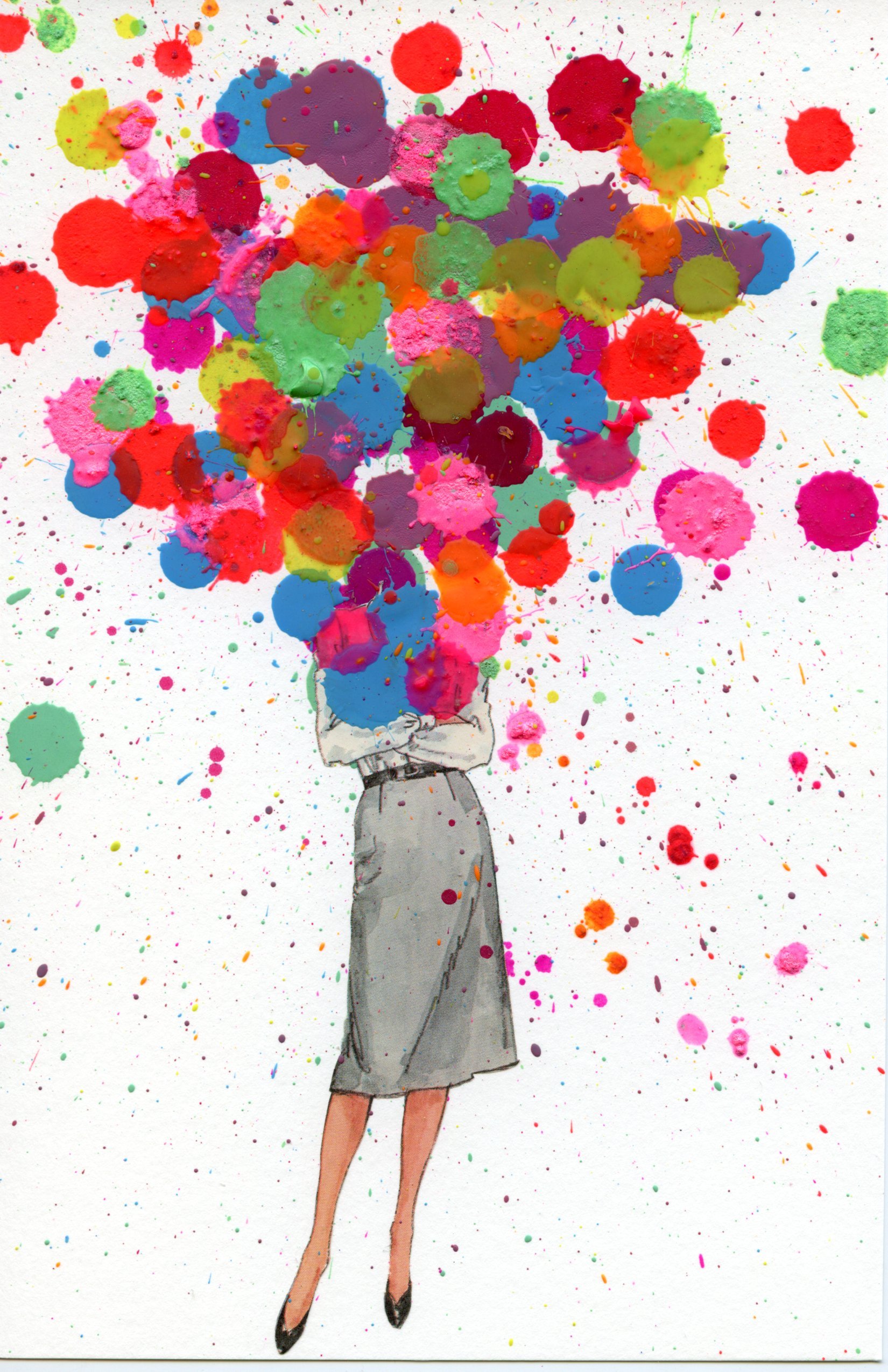

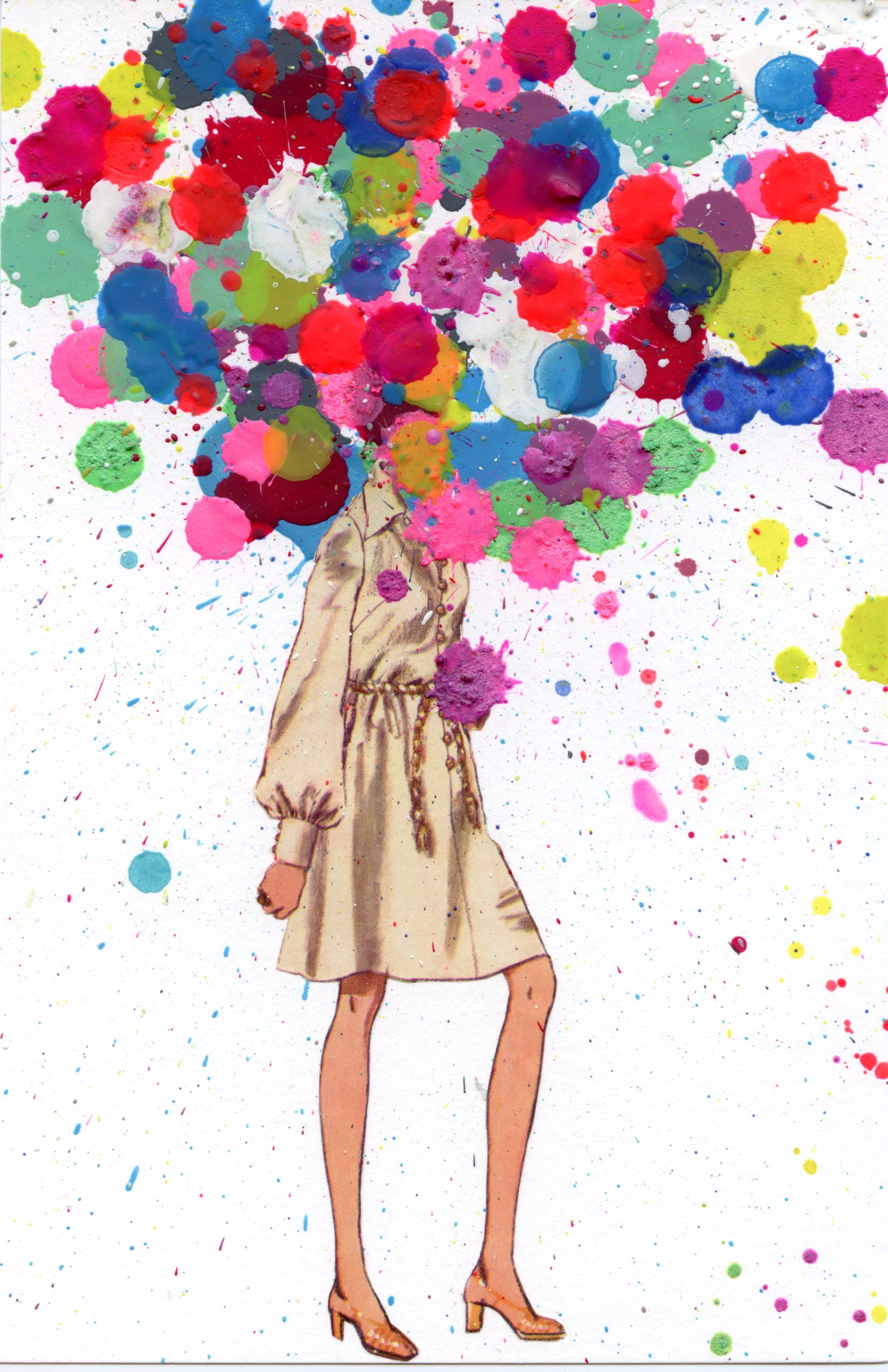

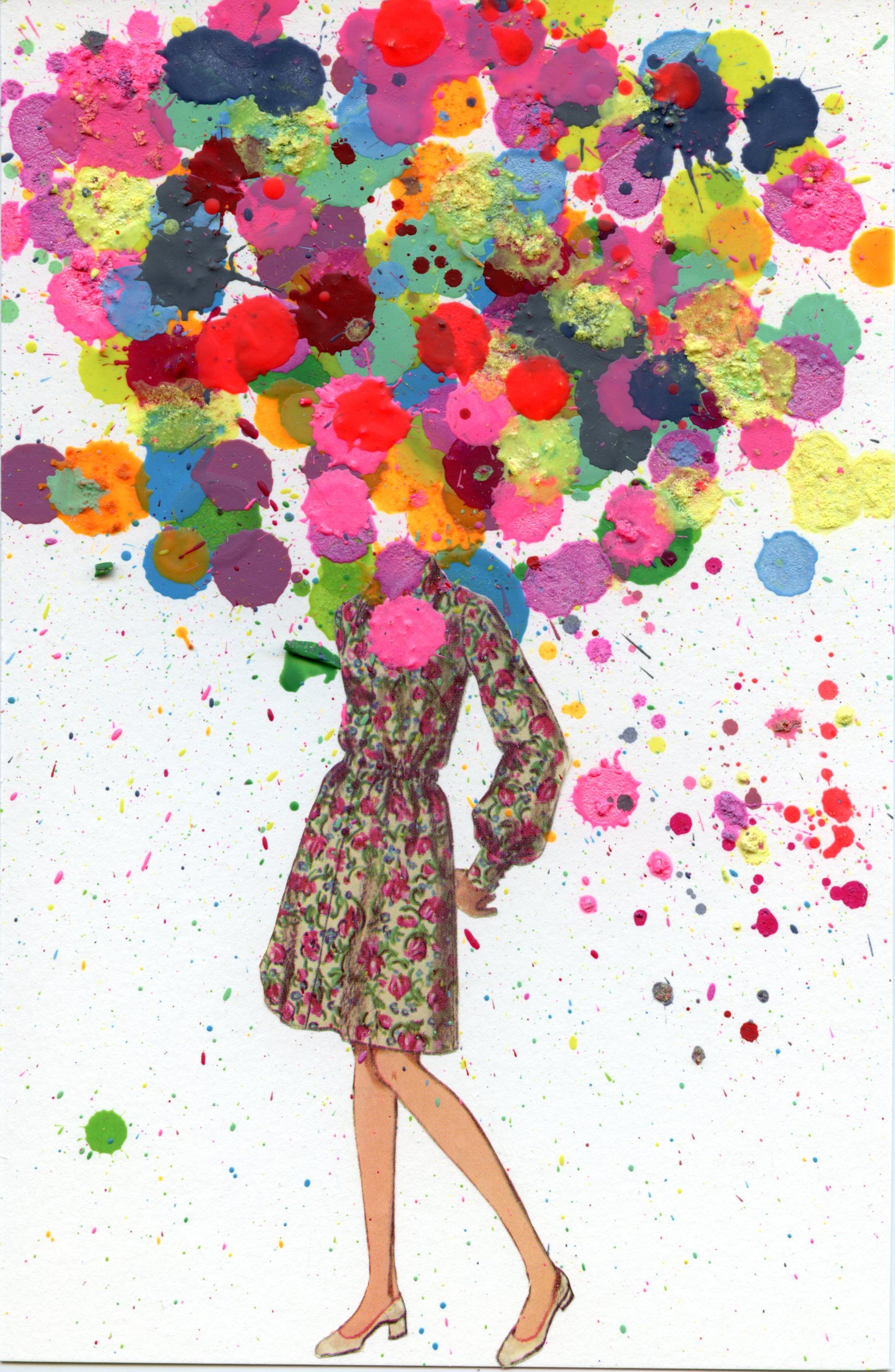

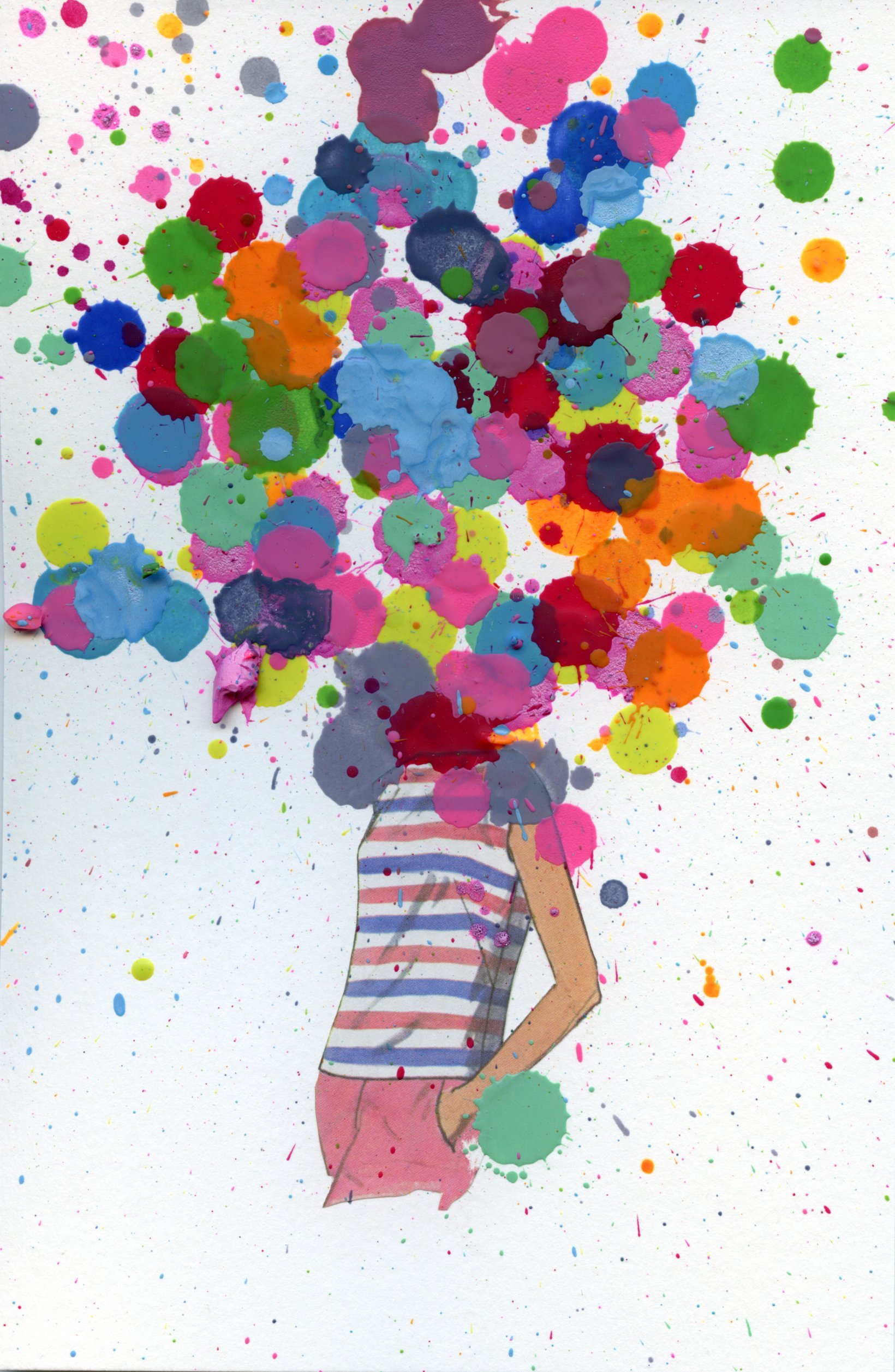

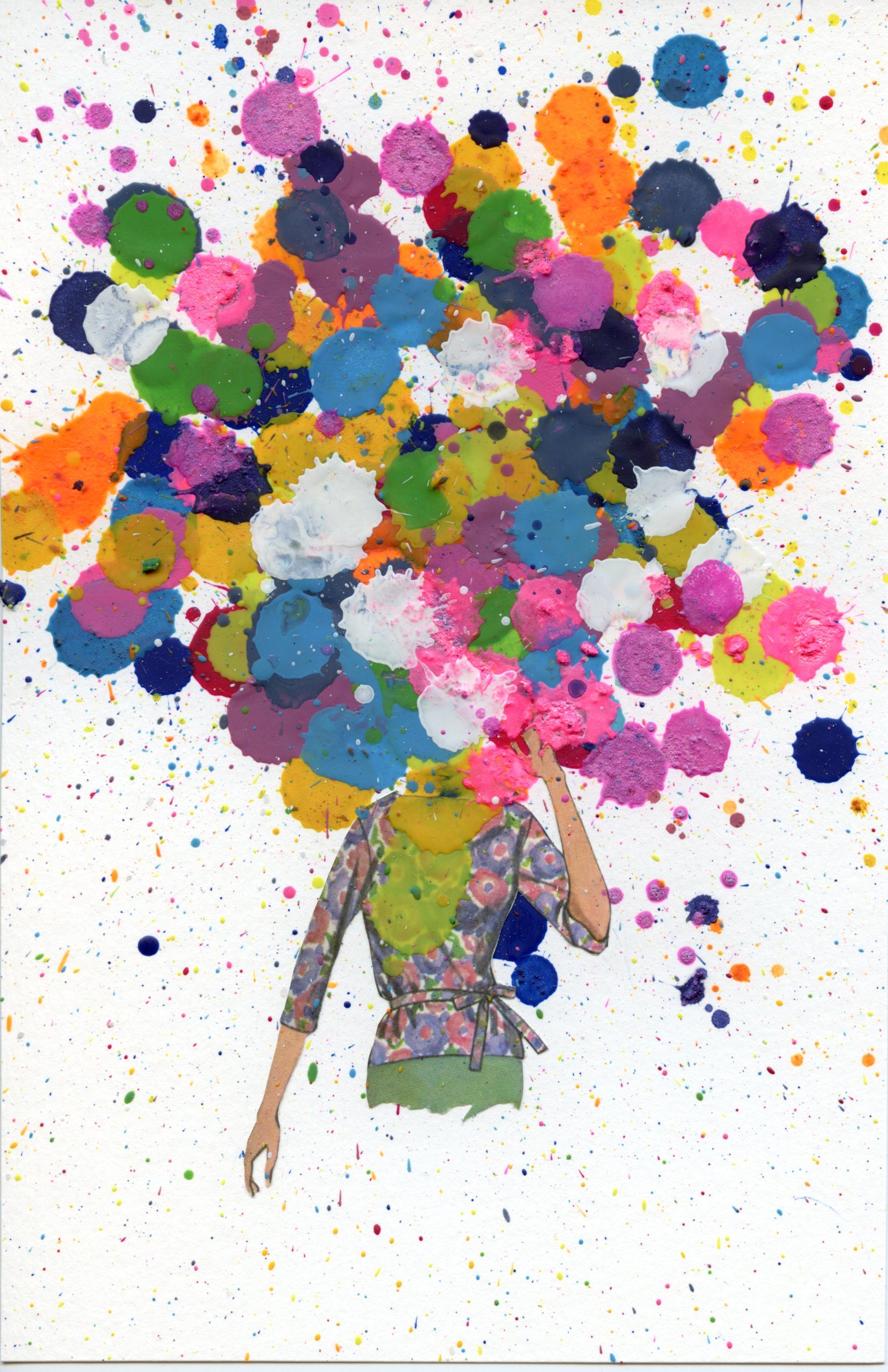

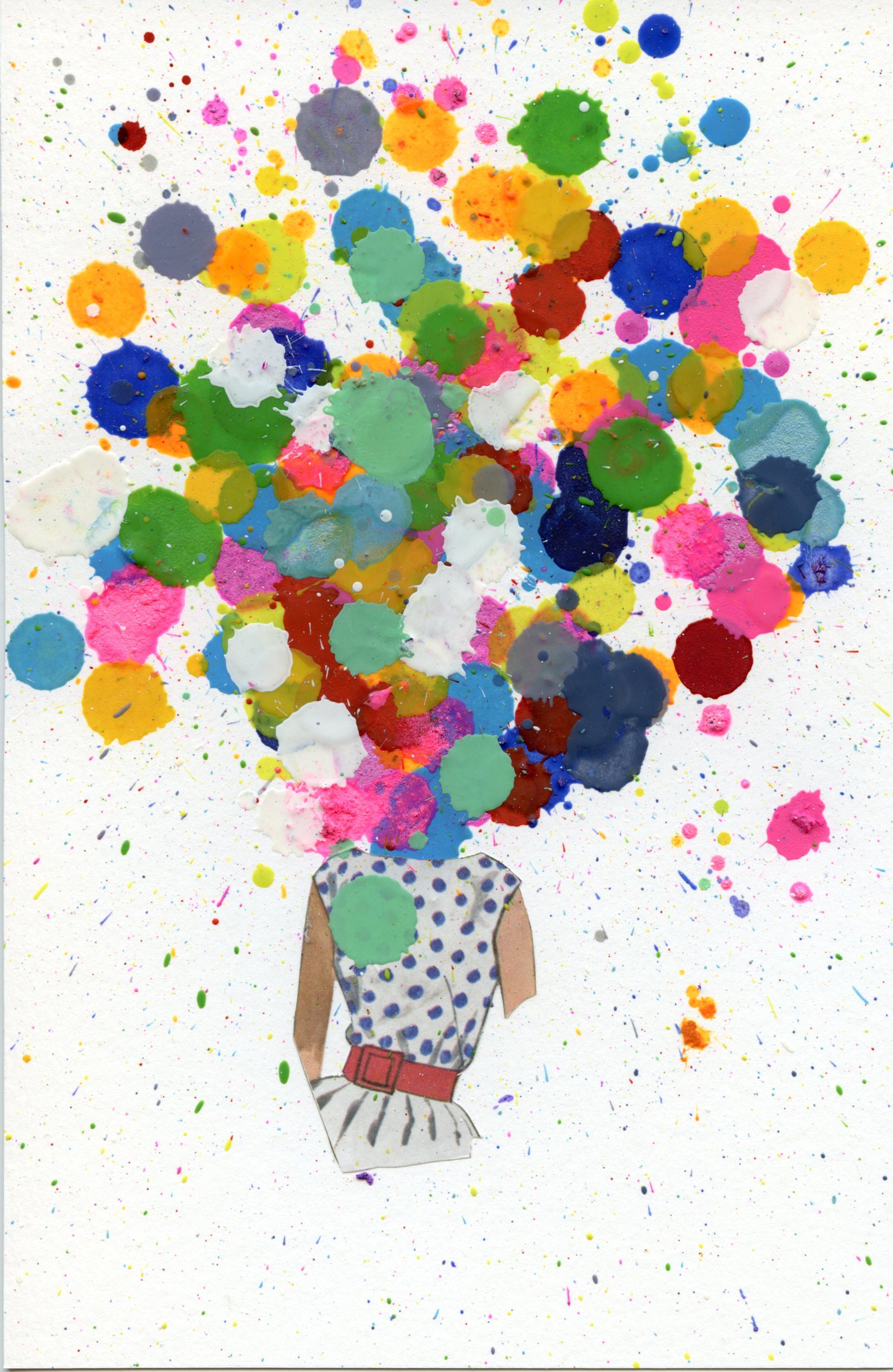

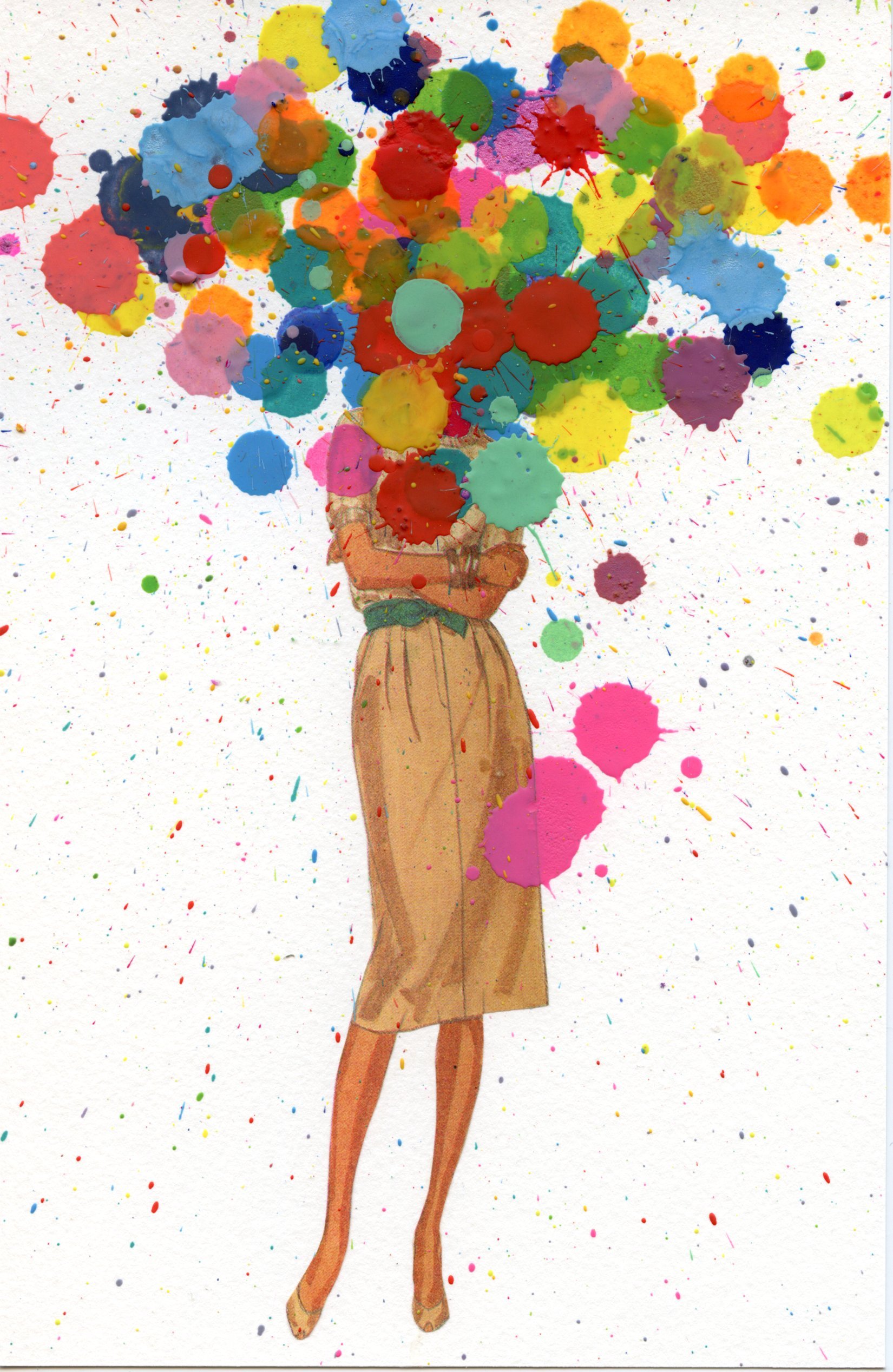

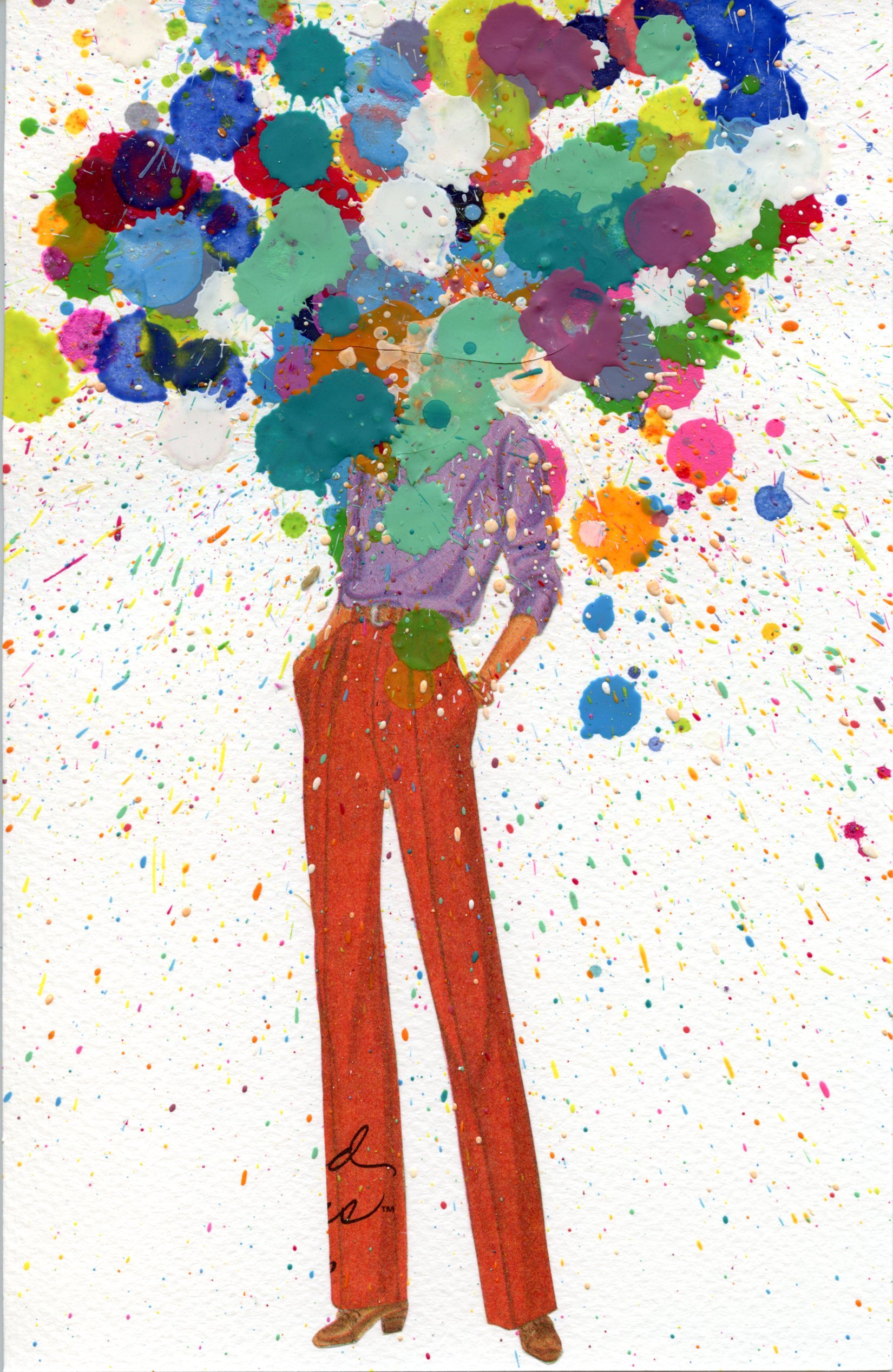

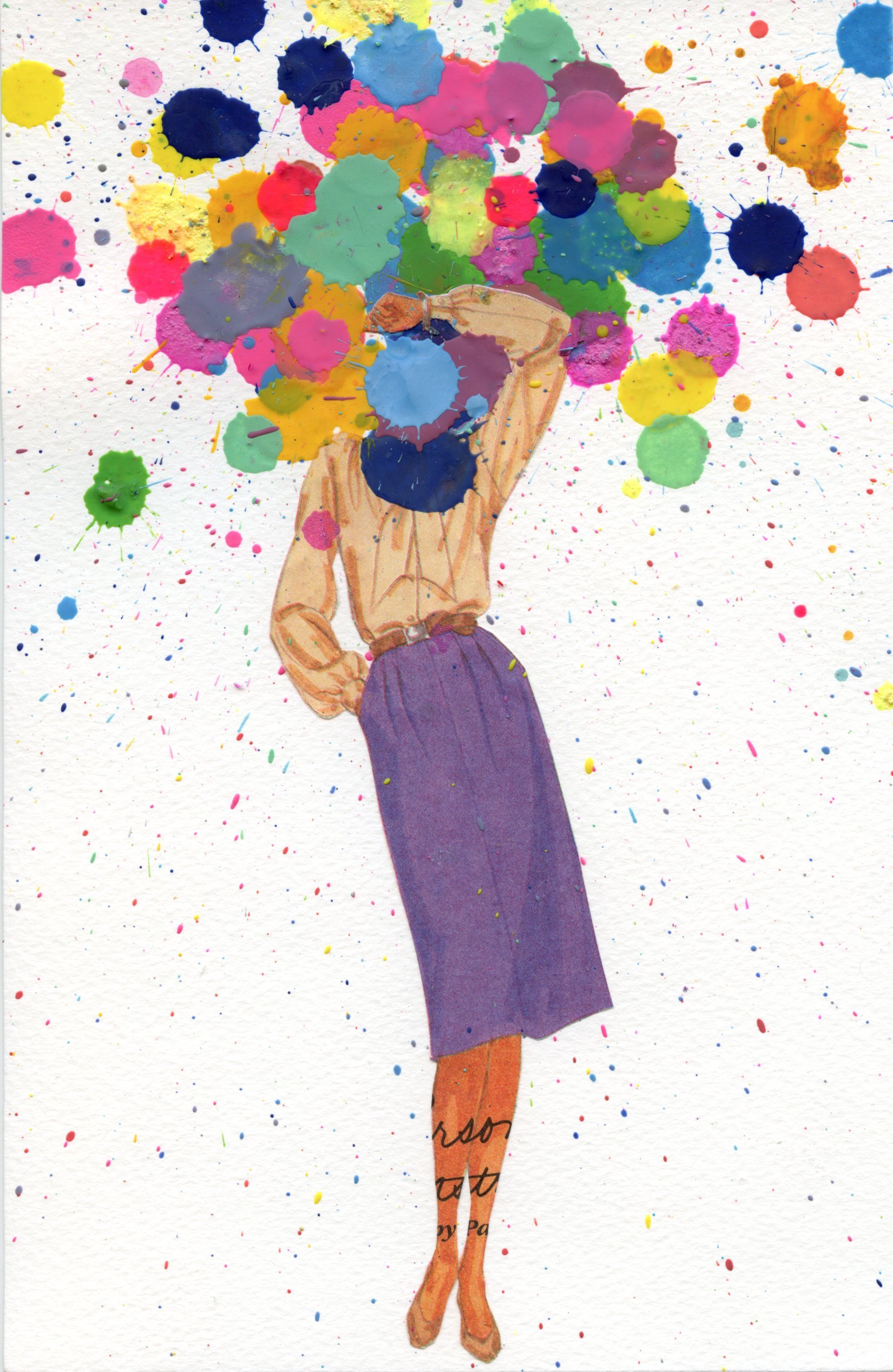

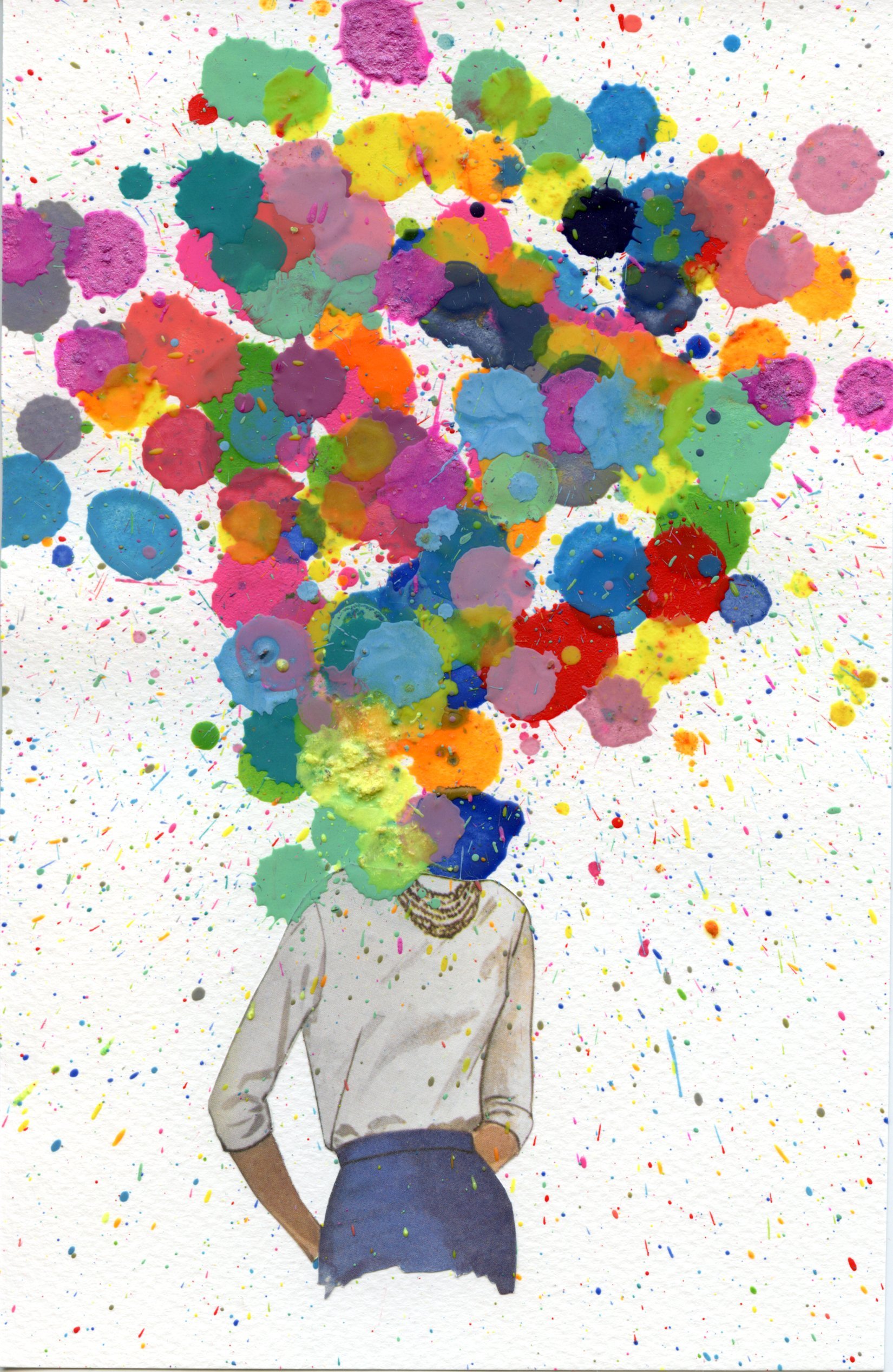

This series lives in the tension between the idealized vision of motherhood I was told to expect and the often contradictory reality I experienced. What I could control, and what I couldn’t. The unpredictable splatters of melted encaustic crayon disrupt the 1950s-era illustrations that once adorned sewing pattern envelopes, evoking a past when housewives were expected to stay home and rarely worked outside the household. This collision of chaos and rigidity echoes the impossible balancing act facing working mothers today: to be competent but not inconvenient, ambitious yet self-sacrificing, present at work while fully available at home.

Each piece embodies the strain of trying to shape a sustainable future for my children while living in a country actively stripping away women’s choices — as mothers, as workers, as humans. I became a mother by choice. A choice that is no longer guaranteed. And with that loss comes a new sense of instability, unsustainability, and anger — at a society that keeps demanding more from working mothers while expecting less of working fathers.

At first glance, I want these works to feel joyful and nostalgic — like the idealized image of a mother who has it all and does it all. But we know that ideal is rarely, if ever, possible, let alone sustainable. Only when the viewer looks closer do they realize this is not just color and play, but also containment and rupture. It’s an explosion — not visible, but internal. Not of bombs, but of expectations, deadlines, logistics, and invisible labor — all orbiting, and often colliding, inside the mind of a working mother stretched to her limits.

This is what it looks like when expectations collapse — when working mothers are expected to do it all, without anyone asking what they want, what they need, or how the system must change to support not just them, but families and society at large.